A History of Furman Sound And Its Grateful Dead Roots

|

By Janet Furman I am the founder of Furman Sound, a pro audio manufacturing company which some have called a spin-off from the Grateful Dead scene of the 70’s. Here’s the story of how I went from teenage nerd to rock’n’roll entrepreneur, with a boost from the Dead. As a child in New York, I had a strong interest in math and science, perhaps fueled in part by a rivalry with my older sister Barbara, who was a high school valedictorian and went into the biological sciences. I studied electrical engineering at Columbia University in New York, receiving a BSEE degree in 1969. I had built a few Heathkits as a teen, but my real introduction to audio came through a part-time job as a tech for the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Studio at Columbia. After graduation, I taught geometry for a year at a private school in Brooklyn, but found it not to my liking. So I headed for the West Coast to pursue a dream of combining my love for music with my education in electronics. I had lots of ambition but no practical experience or contacts in the music industry. In fact, I didn’t yet know a single soul who lived west of the Mississippi.

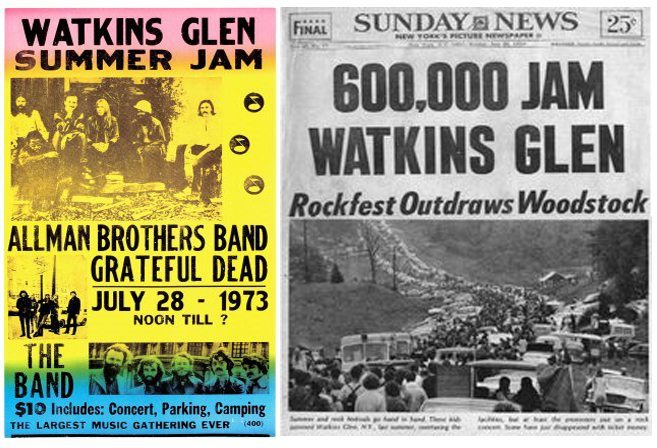

Alembic and the Grateful DeadArriving in San Francisco, I began calling every recording studio in the Yellow Pages. I had a rudimentary knowledge of circuit design, but without any recording experience I didn’t elicit much interest. One of the interviews I got was with Bob Cohen’s fledgling intercom company, but he didn’t offer me a job. When all my calls to established studios drew blanks, I resorted to the last few names, the ones in fine print that didn’t pay for an enhanced listing, probably because they were shoestring operations with no money for advertising. Most didn’t even answer their phones, but someone at the one called “Alembic” seemed interested and asked me to come in for an interview. The name Alembic meant nothing to me, but I was out of options so I gratefully accepted. Soon I found myself hired on at the Alembic Recording Studio as a technician for co-owner Ron Wickersham. Though I had no experience, he must have been impressed with my Ivy League credentials, or perhaps my ability to teach math. This wasn’t a typical career path for an Ivy engineering graduate. Ron must have known I’d have been in line for a much higher paying position in computers, or aerospace, or defense, so he decided to hire me before I came to my senses. But for me, this entry-level position was my dream job. I cared more about breaking into the thrilling world of rock’n’roll, especially the hot San Francisco scene, than about money. I soon learned that Alembic’s main customer, and raison d’être, was the Grateful Dead. I had read about the Dead in Tom Wolfe’s book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which chronicled the story of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, in which the Grateful Dead played a major role. I had even seen the Dead play, at Columbia during the 1968 student strikes, but since they had no hit songs I didn’t know their music well. So, the night I was hired I stopped off at Tower Records and picked up the Live Dead album, recently recorded by the Alembic crew, and Workingman’s Dead, the newly-released acoustic album. This was my homework. I needed to learn about the Dead in a hurry, and I played those albums over and over until I knew every note. At Alembic, Ron was my boss and also my mentor. I learned a great deal from him. My time was spent building prototypes for Ron's design projects, and beefing up, or “Alembicizing”, guitar and bass amps owned by the Dead, the Jefferson Airplane, CSNY, and other local bands. This beefing up process, intended to make band equipment stand up better to the rough handling and rigors of the road, was inspired by the pioneering work of Owsley Stanley (a.k.a. The Bear), another Alembic associate temporarily incarcerated on a drug offense. One of the prototypes I built was a dual tube preamp packaged in a rackmount box. The idea was that a guitarist could plug a guitar into one or both preamps, and the outputs would drive a rackmount stereo power amp. This was a revolutionary concept at the time. Previously, only studios used racks, for fixed, permanent installations. Musicians didn’t use racks – they used all-in-one guitar amps covered in black Tolex. The idea of musicians having equipment racks took a few years to catch on, but this is where it all started. I designed the preamp power supply, circuit board, and rackmount chassis. I called it the F-2B. “F” was a tribute to Fender, whose Twin Reverb triode preamp stage inspired it. “2” because it had two channels, and “B” because the first circuit board layout, designated “A”, had problems and had to be re-done. Alembic turned this into a successful product that they still sell today, 40 years later. I doubt they remember where the name came from. I also repaired whatever came in off the road from Dead tours. Once every few weeks, a truck would roll up and a pack of Dead roadies would emerge, plopping a half dozen defective amps on my workbench for repair. Then they would hang out, drinking beer and passing joints, while I tried to look busy. After they’d seen me often enough to be a familiar face, it was time for my initiation. Sparky and The Kidd put a couple of drops of pure acid, disguised as Murine eye drops, into my beer. I didn’t notice a thing for an hour. It hit me while driving my clunker car home that night. Rush hour traffic on the Bay Bridge was never so fascinating. No one ever said so, but from then on, I was part of the crew, too. Once I learned the ropes I was asked to go on the road with the Dead to help with live recording. I was utterly thrilled at this opportunity, and jumped at the chance. I would be working with Bob Matthews, Betty Cantor, and Wizard, another tech who came to Alembic soon after me. Bob was the Dead’s producer and Ron Wickersham’s partner in Alembic; Betty was the Dead’s original recording engineer. At the time, they were a couple, though that didn’t last long. My role was to pack and unpack recording equipment, set it up and calibrate it, set record levels when the band did their sound checks, and change tape reels between songs so that no music was missed. This was no small job, since we recorded most concerts on gigantic reels of 2" magnetic tape on an Ampex MM-1000 16-track, a then-state of the art system that Ron had repackaged into flight containers so it could be air-freighted to each Dead venue. A full reel weighed about 30 lbs, and those heavy weights had to be handled with great care and speed. At 30 inches per second, the tape flew by and reels had to be changed frequently. Early in 1972, the Dead scheduled an often-postponed European tour in which the entire Dead family – me included! – would be able to accompany the band and travel in style. There were to be 28 concert dates in 17 cities over a seven week span in April and May. Every single gig was to be recorded onto 16 track tape, and the best performances would be made into an album to be released after the tour. Nearly 50 people, including the band, managers, road crew, recording crew, lighting crew, truck drivers, office staff, travel agents, and a smattering of wives and girlfriends (“old ladies” was their derisive moniker) would be traveling on three luxury buses and a variety of plane and ferry connections. I packed my bags and flew to London on April 1. The Europe 72 tour was a quintessential Dead time. The band members were still young and in their prime. Life was a routine of afternoon setups and sound checks, inspired performances in the evenings, and all night partying back at the hotel. Mostly I kept a distance from the bad behavior and carrying-on, occasionally directing groupies to the band members' rooms. One morning I overslept and missed the crew bus to the venue. I frantically ran to the hotel lobby to see if anyone else was in the same predicament. The only familiar face was that of Jerry Garcia, who invited me to ride over with him. After a leisurely breakfast, a stretch limousine picked the two of us up. As we approached the hall, we could see a long line of ticket holders wrapping around an entire city block. When the limo dropped us at the stage entrance, a phalanx of cops had to clear a path for us through the adoring crowd. It was like a scene from “A Hard Day’s Night” come to life. After the tour was over and the entire entourage and the mountains of equipment returned to California, it was time to listen to the recordings. The band members remembered specific songs from specific nights that they wanted to hear, so we dug those out of the enormous tape archive and set up rough mixes. Eventually they selected the best performance of each song, though none were good enough. Virtually every vocal was overdubbed in the Alembic studio that summer (except Pigpen’s, mainly because he was too sick to come to the studio, and died not long afterward.) Some instrumental solos were also overdubbed. The tracks were well enough isolated that a casual listener would never know. The final product, a triple LP entitled "Europe 72", quickly went platinum. It was one of the Dead’s finest albums, a favorite of many Dead fans even today. Not every Dead concert was recorded to 16 track. I only traveled with them for those that were, or occasionally I came along as the equipment tech. One memorable tour in July, 1973 included a stop at the Watkins Glen Summer Jam, held at the famed auto raceway. This all day outdoor concert featured just three super groups – the Grateful Dead, the Band, and the Allman Brothers. But that bill was enough to attract the largest crowd in rock history, if not in all of American history – 600,000, easily topping Woodstock’s smaller but better remembered crowd of 300,000. The Dead would need a massive amount of amplification to reach all those people. At the time, they insisted on using only McIntosh 2300 power amps, an audiophile rather than pro audio product, made in small quantity and hard to find on short notice. The McIntosh factory happened to be near Watkins Glen, in Binghamton in upstate New York. We were already backstage at the concert, and every road in the area was clogged with concert traffic. My assignment was to get five more of those giant amps, any way I could. Sam Cutler, the former Rolling Stones road manager now working for the Grateful Dead, handed me $6000 in cash and the use of a helicopter and pilot. Though it was a weekend and the McIntosh factory was closed, I tracked down the owner at his home. The pilot flew me from the venue to downtown Binghamton. Helicopter landings there were not an everyday affair, and there was great media interest. Flashbulbs popped and reporters stuck microphones in my face. In the summer heat, I was wearing only shorts and a concert T-shirt, with the cash wadded up in my pocket. I met up with the owner, who drove me to the factory and sold me the amps off the production floor. We drove back to town in his station wagon, his wife and kids aboard on their way to a summer vacation, and transferred the amps into the copter. At over 100 lbs each plus two people, it was a heavy load for a small helicopter. We had a very scary moment as we took off, coming within inches of crashing into a highrise building. But back at Watkins Glen, the sight of that enormous crowd from the air was unforgettable. In the moment I landed, delivering the goods, I became an instant hero.

The Watkins Glen poster and New York Daily News story. This needs no explanation. |

Janet |

| The Evolution of Furman Panel Design

The original PQ-3, 1975. Note that the panel was not silk-screened but etched and filled with green enamel, in the style of old-time machinery nameplates. This meant the lettering was raised above the background and could never be worn off. I really liked this look, but it was impractical. Nevertheless, the original PQ-3 was re-issued in 1998 in response to a nostalgic demand.

Second generation PQ-3 and PQ-6, 1981. After a few years, the reps told me to get serious and drop the "Christmas tree colors." So we joined the herd and adopted black, silk-screened panels across the entire product line, but I insisted on clinging to red knobs.

Third generation PQ-4, 1986. Tastes in panel design were changing, and Furman responded with "safe" colors that would appeal to our overwhelmingly male customer demographic: blue, black, and grey. We called the grey blobs "hockey sticks." To add flair, we added the words "Signal Processing" or "Power Conditioning", under the logo - in script writing. Using smaller knobs, this updated parametric squeezed in a fourth EQ band.

Fourth generation, 1993. The latest trend in panel design abandoned black and introduced white, but only temporarily. This was one of six models of graphic equalizers made by Furman.

Reference series, 2000. These beautifully designed power conditioners feature a combination of black and clear brushed aluminum, with a three-dimensional logo. The lack of rack ears is indicative of Furman's gradual shift from pro audio to the high-end consumer market.

The specially modified Ampex MM-1000 16-track recorder that was used to record the Grateful Dead'sa Europe 72 album. |