A History of Furman Sound And Its Grateful Dead Roots

|

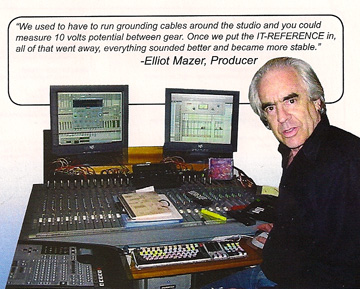

Continued from <previous page> His Masters Wheels Eventually, Alembic got out of the Grateful Dead servicing business in order to concentrate on manufacturing guitars and basses, a business it is still in today. First they sold off the early sound system, the one that later evolved into the famous Wall of Sound. The buyer was the Grateful Dead. By the end of 1973, they sold the studio at 60 Brady Street. The new owner was Elliot Mazer, a New York rock producer who renamed it His Masters Wheels. Elliot hired me to work for him, so I stayed with the studio in San Francisco while Alembic moved north to Sonoma County. First, we updated and remodeled it, installing a top of the line Neve console and Studer 16 track. Elliot knew everyone in the music industry. I began to broaden my horizons beyond the Dead and their offshoots. With Elliot as producer, I did studio and live recording for a number of big name and up-and-coming acts. We flew to Toronto to tape Gordon Lightfoot in concert. I overdubbed and remixed a posthumous Janis Joplin album. One day in September, 1974, Steve Miller booked time to record a song, and possibly an entire album. They were to arrive that evening at 8 pm, and Elliot asked me to engineer it. That night became a turning point in my life. Like many studios of the era, His Masters Wheels would book demo sessions with local unknown artists at deeply discounted rates during slack periods. If a name act came along with a full-rate booking, the demo could be bumped. That was what happened that night. I had scheduled a late afternoon demo with a big band that had over a dozen musicians. I would have to cancel their session in order to have time to be set up for Steve Miller. I phoned as many as I could reach, but the time was so short I couldn’t reach them all, and they began to arrive only to find out they’d been bumped. Some didn’t understand and were angry, and I had to try to defuse the situation. After a stressful afternoon, at 8 pm I finally had mics in place for Steve Miller and fresh tape ready to roll. But he was late. I fretted for the next few hours. I was keenly aware that if I’d known he would be so late, I could have done the earlier demo session and avoided inconveniencing and angering so many people. By 10 pm I was tired and cranky. Miller did show up, with his band – at midnight. I had been up all day and was ready to sleep, not start a major project. Miller was drunk, or stoned, or both. He was loud, rude, and abrasive to me. We had a distinct failure to communicate. The song we worked on was called “Fly Like An Eagle.” It seemed to have potential, but by the time we quit at 9 am I was so exhausted I didn’t care. I went home, got a few hours of sleep, came back and told Elliot I wasn’t going to work with that jerk any more. “Get someone else to do it,” I insisted. “He treated me like a piece of furniture.” Elliot told me I was making a mistake. Miller was already a big name, and engineering an album with him would be “a feather in my cap.” Besides, we needed the business, and Miller would run up a very big bill in the course of making an entire studio album. Didn’t I know the customer is always right, even if he’s a jerk? It was my responsibility to keep customers happy. But being young and brash, and not knowing much about business realities, I stood my ground and refused to work with Miller again. The next day, Miller decided he didn’t like our studio and left to complete his project at the Record Plant, our cross-town arch-rival. Elliot was furious and blamed me. In the course of a few days I had gone from being Elliot’s favorite to being fired.

Furman Sound Service As I glumly contemplated the reality of being unemployed and having lost the job I had dreamed of for so long, I wondered what would be next for me. I wanted to stay in the music industry, but I had learned a lesson. Rock stars could have big egos and were not always pleasant to be around. Recording sessions could go on all night, and I liked my sleep. I had taken up running a couple of years earlier, and now I considered myself an athlete. Running eventually became an obsession for me as I began a regular training program and became more and more competitive. Perhaps I’d be better off without the late nights, the smoking, the drinking, and the drugs. I thought about my time with Alembic and how I had turned a casual idea into a commercial product, the F-2B. I had done it once, perhaps I could do it again. And surely there was no magic to running a business. Ron and Susan Wickersham were nice enough people, but I was unimpressed with their management skills. Surely I could do as well, if not better, once I figured out the basics. If I were my own boss, I could set my own hours! Never again would I have to awaken to the sound of an alarm clock. I was wrong about that, but at the time it was an important goal. I even had an idea for a product I could make. At Alembic, we had often discussed the vast differences between the capabilities of pro audio equipment and those of musical instrument equipment, wondering why musicians had only volume, bass, and treble knobs on their guitar amps when they could have so much more control over their sound. I had seen and been fascinated by a new and hot studio equalizer – a “parametric” equalizer. It allowed almost limitless variations of tone adjustment. Why not make a parametric equalizer in a box that you could plug a guitar into? It could be a preamp, like the F-2B, but never mind the tubes. They were outdated and unreliable. I would create a modern equalizer/preamp using integrated circuit op-amps. When I started Furman Sound Service a few days later, my immediate goal was simply to set up a one-person repair shop to generate some income. My location was a tiny unfinished loft upstairs at 60 Brady Street – the same building that housed His Masters Wheels! Now that I was no longer an employee, Elliot and I had become friends, and he had no objection to subletting me this small, unused space. It was an ideal location – the rent was cheap, there was a guitar shop, Stars Guitars, immediately adjacent which could refer business to me, and there was a steady stream of musicians in and out of the building at all hours. I did not foresee where this humble origin might someday lead. Though I had the idea to design a parametric equalizer/preamp, I knew that would take a while and I would have to make a living in the meantime. So I did what I could. I repaired and customized guitar amps. I maintained Elliot’s studio equipment. I taught a class in recording studio techniques. I wrote a few magazine articles for Guitar Player and some of the studio trade mags. I engineered occasional freelance sessions at HMW and other studios around town. And I worked on the parametric design. At first I shied away from making it rackmount. Racks for musicians was still a very novel concept. I thought the parametric might sell better as a floor stomp box, so I worked toward that. Once I had a working prototype, a company called Norlin got wind of my design and expressed an interest in licensing it under their Maestro brand. I was intrigued. They packaged my circuit board in a box with the Maestro logo and test-marketed it at NAMM, the big music trade show. But it didn’t attract much interest there, and Norlin backed away. There were just too many knobs for a product that would be sitting on the floor. I decided it had to be rackmount. It would be a groundbreaking product. Even if the average musician didn’t understand, cutting-edge musicians would. And those were exactly the kind of musicians who hung around 60 Brady Street. It took just over a year to design and build the production prototype of the “Furman PQ-3 Parametric Equalizer/Preamp”. The day it was finished, I took it home and stared at it for hours, bursting with pride. I had just enough money to buy parts for 20 units, which I built and sold myself, all to Brady Street regulars whom I knew personally. The very first unit, serial number A00001, went to Jerry Garcia. Then I ran out of customers. |

The First Furman Sales Literature

This was the announcement of Furman Sound Service's debut, in September, 1974. To save typesetting costs, I made the headlines with rub-on type, in the days before personal computers.

Click here to see the inside pages

Look who became a Furman endorser many years later - it's my old boss from His Masters Wheels, Elliot Mazer! This ad came out in about 2003.

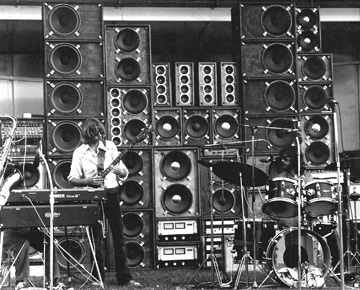

Part of the Grateful Dead's "Wall of Sound" PA system, seen in the late 1970's. A PQ-3 and a TX-2 are visible at far left, in Jerry's equipment stack. The amps at bottom center, in Phil's stack, are the weighty McIntosh 2300's. |