A History of Furman Sound And Its Grateful Dead Roots

|

Continued from <previous page> Furman Sound Service had been created without benefit of a business plan, and its owner had only the most rudimentary knowledge of sales and marketing. I knew it was time for some homework. There was a buzz, an opportunity here. I didn’t want to miss the boat. I knew I would have to keep the production going and build up some inventory. With the proceeds from the sale of the first batch, I bought parts for another hundred units and hired two assemblers to build them – the first two Furman employees. (One of those assemblers was Richard Bosworth, who later went on to be a well-known Hollywood record producer.) I also knew trade shows were key. I would have to go to NAMM, and perhaps AES (the recording/pro audio show), to develop sales channels. I built a small trade show booth, loaded it in my car, and drove it to Los Angeles for AES. Furman was the smallest exhibitor at the 1977 AES. Normally the smallest space was a 10' x 10' floor area. But a large pillar blocked access to half of one particular 10' x 10' space, The AES management let me rent the 5' wide space at a price I could just barely afford. Among the visitors to my booth was Paul Rothchild, a name familiar to me as the producer of one of my favorite bands, the Doors. We hadn’t met before, but Paul had heard of Furman from the Alembic folks and some other small but promising musical instrument (MI) companies. All these companies had intriguing products but poor distribution. It was Paul’s idea to sign us to an exclusive distribution deal with a company he would create and back financially – Rothchild Musical Instruments. The offer seemed too good to refuse. They would buy virtually all the PQ-3’s I could produce, warehouse them in San Francisco just two blocks from my Brady Street loft, and sell them wholesale to music retailers everywhere. I signed on. So did Alembic, as well as the makers of Taylor and Larrivée guitars, Bartolini pickups, and several others. To assist Furman sales, Rothchild would not only develop an advertising program at their own expense, but also provide Tolex-covered single rack space boxes with handles, as an option for those who weren’t quite ready for the musician-rack concept. Thus began a halcyon period of my two-man assembly team cranking out PQ-3’s as fast as they could make them, delivering them to Rothchild every few days by walking them around the corner stacked 8 high on a hand dolly. Payment checks arrived regularly. I was surprised and slightly flustered, because it was substantially more money than I had ever made as an engineer. I began work on a followup product, an electronic crossover called the TX-2. And I began to look around for a larger space. Furman Sound, Inc. Later that year, I moved the company up to San Rafael, across the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County. I incorporated it, changing the name to “Furman Sound, Inc.” No longer was Furman a service business. We were now focused solely on manufacturing the PQ-3 and TX-2. But trouble was brewing. The checks from Rothchild began to slow. Their cash flow problems impacted not only Furman, but all their brands. Without cash we couldn’t buy inventory, and since we couldn’t sell to anyone else, we were stuck in limbo. I chafed to get out of the contract. After a protracted showdown, I negotiated a buy-out. Fortunately, by then I had learned a lot more about how musical instrument products were distributed. I quickly offered a job to Lary Collins, who had been Rothchild’s sales manager. There was no one in the world who knew more about selling Furman products than Lary. With Rothchild’s empire crumbling, he accepted. Now, with three assemblers, a shipper, a sales manager, and me, Furman Sound employed six people. We began selling directly to retailers without a distributor middleman. Though my payroll costs were higher, profit margins were higher, sales volume increased, cash flow improved, and dealers clamoring for product were mollified. The company continued to grow. I was able to buy a modest home of my own. The next Furman product would be another repackaged classic: a spring reverb system in, of course, a rackmount box. It was designated the RV-1. By 1981, we had grown to about a dozen people, and were outgrowing our rented space in San Rafael. I bought a tin-roofed 12,000 square foot building that had once been an auto repair shop, located a few miles away in Greenbrae. That funky place became Furman Sound’s home for the next 16 years. Of all the aspects of running a manufacturing and wholesale sales business, I found that I enjoyed the creative process of marketing best. So I concentrated my personal efforts on advertising, sales literature, and trade shows. I continued to be the final arbiter on decisions concerning new product development, but willingly relinquished my role in circuit design to a new engineer. That engineer became the nucleus of an engineering department that eventually grew to six people. We introduced one or two new signal processing products a year, such as limiter/compressors, noise gates, graphic equalizers, rackmount mixers, small power amps, and the like. It was our practice to introduce new products to our network of sales reps each year at a sales meeting at the NAMM show. At the 1985 sales meeting, I did a bit of market research on a new product idea I’d been toying with. I told the assembled 18 reps, each representing a different US sales territory, that I was thinking of making a rackmount AC power control center. You would plug all the equipment in the rack into it, and it would have a handy master on-off switch and a meter to show that the AC voltage was OK. It would also have some surge suppression features to protect the equipment. It wouldn’t be a signal processor like our other products, but it seemed to me like something that would meet a need for anyone who had an equipment rack. The reps thought it was a good enough idea, but it didn’t generate more than modest interest. The rep from Southern California did suggest that adding some lights, to illuminate the equipment in the rack below it, would be a nice enhancement. I took that thought home with me. It turned out to be a very, very, very good idea. I had my engineering people look into some kind of light fixture that would be recessed when not in use, but could pop out somehow to cast a beam from an angle that would minimize shadows. We tried various rectangular doors and drawers, but they were mechanically complicated, so we eventually settled on two round aluminum tubes that would slide out. Their diameter would be large enough to accommodate 12 watt bulbs, which would seem quite bright on a dark stage. We added threaded caps to make bulb replacement easy, machined plastic bearings so the tubes would have a nice smooth feel when they were pulled out, and a dimmer to adjust the brightness. I called the contraption the PL-8 Power Conditioner and Light Module. The “8” referred to the eight AC outlets in the rear. The introduction of the PL-8 marked a major turning point in Furman Sound’s history. It was an immediate, runaway success. Everyone loved the pull-out lights. Soon every rack in the pro audio world would be topped off by a PL-8. The demand was enormous, dwarfing anything that came before it. The PL-8 changed Furman from a sleepy little company to a high volume, modern manufacturing plant. It didn’t happen overnight. There were growing pains, staffing shortages, cash flow issues, material shortages. I had to scramble to find qualified, experienced management people who could handle a rapid expansion. It was all new to me – I was, after all, a rock’n’roll engineer, not an MBA. It was an exciting time. I had to learn fast. One upshot was that the direction of the company began to shift. We began a long, slow turn away from signal processing products and toward AC power conditioning and distribution products. The PL-8 spun off a host of variants. There were (and still are) models for higher and lower voltages and currents, models with and without meters, LED meters, digital meters, even built-in guitar tuners. Higher priced models stabilized voltage or isolated it from the power line. We made big 100 amp distros for use on large performance stages. We made power conditioners that could be turned on locally or remotely, or powered up equipment in timed sequences. We even made low-cost PL-8 clones under a different brand name, RackRider, to compete with proliferating offshore knockoffs. The emphasis on power is still going on as I write this in 2012. Furman now makes only a few signal processors. The vast majority of its product line are power-related. Furman “Sound” has become a misnomer, but the current management hasn’t seen a pressing need to change it. Aside from getting “guest list” status at occasional concerts, I didn’t see much of the Dead in the mid-80’s. But one incident stands out in my mind. I was in the airport in Chicago, catching a flight home from the Summer NAMM show. A familiar face approached. It was Jerry Garcia, walking toward me accompanied by Ken Kesey, now even more famous for writing the bestseller One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. I had met Kesey briefly a decade earlier on a Dead tour stop in Oregon, but of course he didn’t remember me. Frankly, I wasn’t quite sure if Jerry remembered me, either. Jerry was so besieged with admirers and hangers-on, why should he remember someone who had been a peripheral part of his crew years ago? But when I smiled and greeted him, not only did he know who I was, he treated me like a long-lost cousin! He introduced me to Kesey and the rest of their entourage, invited me to hang out with them while they waited for their plane, and proudly told the story of how I’d started a successful company after serving an apprenticeship with the Dead. That meant a great deal to me. Jerry wasn’t like so many other rock stars. He was a genuine, kind-hearted, down to earth human being. When it was time to leave and board our planes, Jerry made me an offer I was only too glad to accept. He said he’d do an endorsement ad for Furman, and he’d get Bob Weir on board, too. They came through on that promise. Each posed for a photo while holding a stack of Furman products. The finished ads ran in Guitar Player and other magazines. They were the first of a long series of artist endorsement ads. Ten years after the PL-8 revolution, Furman was bursting at the seams. Every inch of our Greenbrae building was crammed with people and inventory. A dozen rented trailers filled our parking lot and the surrounding streets to house the overflow. Our neighbors were complaining. It was time to move. I was unable to find a suitable building in Marin County, so I looked north to southern Sonoma County. In Petaluma, I bought a two acre plot that had previously been farmland and started construction on a new, modern 32,000 square foot office/production facility. We anxiously awaited the moment when it would be ready for occupancy. We moved in January, 1997. We celebrated the move with a big party complete with several bands, including my own oldies cover band, at the time called Totally Naked. I was the bass player. Furman was riding high in its new home. Annual sales hovered close to $10 million. I took great pride that the company had created over 70 good jobs for local people, many of whom were able to buy homes and fulfill their own dreams. In two years, we would celebrate our 25th anniversary. I decided that 1999 would be the perfect time to sell all or part of the company so I would be able to enjoy more free time. Furman Under New Ownership I hired an investment banking firm to search for a buyer. After an excruciating marketing process, they presented me with four competitive offers. I did not want an abrupt separation. I turned down the highest offer, from another pro audio company, to accept one that would allow me to retain 15% ownership, have a seat on the Board of Directors, and be employed as a consultant for three years. The new owner was an investment fund. The management they put in place knew mergers and acquisitions, but nothing about our industry. I didn’t realize it until too late, but they were only looking to flip the company in a few years and make a quick profit. That approach was an extremely poor fit with Furman’s corporate culture. As a minority board member, I tried but was powerless to stop them. They fired some of my most devoted, hardworking managers and replaced them with unqualified family members of the new CEO. Morale plummeted, and sales followed in a downward spiral. The highly leveraged buyout was meant to be financed by Furman’s future profits, but they drained the cash and maxed out the company’s lines of credit. In 2004 they defaulted on a loan and the lender foreclosed, taking over operations. The stockholders, including me, lost most of their stakes, and a new board was appointed that didn’t include me. The new owners, a finance company that could trace its ownership to Warren Buffett’s empire, tried to right the ship but too much ground had been lost. After a couple of years they gave up and accepted a buyout offer from Panamax, a nearby power conditioning company which specialized in low-cost consumer products. After seven years in the wilderness, at last Furman was in better hands. Panamax knew power products, and Furman’s emphasis on the pro audio, sound contracting, and high-end consumer markets made for a synergistic fit. Since Panamax was also based in Petaluma, the two companies knew each other well. In fact, Furman had manufactured a few products for Panamax under the Panamax name as far back as the early 1990’s. Panamax quickly moved to control costs and combine operations. They moved Furman out of its beautiful, custom-built home, squeezing it into their own much smaller space a half-mile away. Most of the surviving management people kept their jobs, but sadly, the production team was dissolved. It went the way of so many other American manufacturing job forces – to China. Though I was no longer involved with Furman’s operations, I still kept in touch with many company old-timers and was painfully aware of this development. Though a few products had been made in China even back when I was still CEO (mainly the low-cost RackRider line), now all production had been moved there. Eventually, Furman and Panamax integrated fully. Morale has been much improved, and, drawing on the combined experience of both companies, some great new Furman products have been introduced. Both companies are tiny divisions of a large corporation called Nortek, Inc., based in Providence, RI. According to its web site, “Nortek (through its subsidiaries) is a leading diversified global manufacturer of innovative, branded residential and commercial ventilation, HVAC and home technology convenience and security products. Nortek offers a broad array of products including: range hoods, bath fans, indoor air quality systems, medicine cabinets and central vacuums, heating and air conditioning systems, and home technology offerings, including audio, video, access control, security and other products.” In December, 2009, Nortek emerged from a bankruptcy more or less unscathed, in which $1.3 billion in debt was eliminated. Nice work, Nortek. Most of the subsidiaries seem to manage their own affairs with only minimal oversight by corporate headquarters, an arrangement that suits the Panamax/Furman culture well. In 2016, after continuing problems at the corporate headquarters, Nortek was in turn acquired by the British engineering turnaround company Melrose Industries PLC, for $2.8 billion. Melrose, it was said, was particularly drawn to Nortek because of its ventilation and air handling businesses. Furman and Panamax are now two of ten brands merged under the name Core Brands. Core Brands includes other lines in the custom integration business, such as SpeakerCraft, Niles Audio, Elan, Xantech, and more, and is in turn part of the Audio, Video & Control segment – which itself is part of the Security & Smart Technology division. Nortek's other two divisions are Air Management and Ergonomics. Profit margins are now said to be increasing. What a long, strange trip it's been.

I would like to acknowledge the contributions of three close friends and long-time senior Furman managers: Gary Kephart, Chief Engineer and briefly, during the first transition to new ownership, President; the late Joe Desmond, VP of Sales and Marketing; and Earl Norgard, Chief Financial Officer. Guys, I couldn’t have done it without you.

© Janet Furman 2018. All rights reserved. You can contact Janet at |

Furman Stickers

1977

1979

1984

1988 |

|

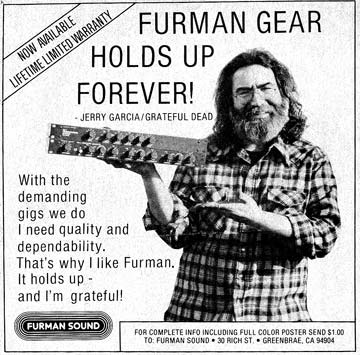

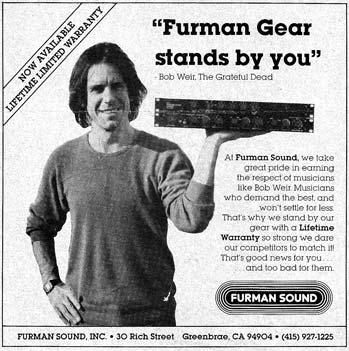

Grateful Dead Endorsement Ads

These two ads appeared in various guitar and pro audio mags around 1983. The photos were shot in the street outside of the Dead's rehearsal studio, Club Front, by photographer and Dead chronicler David Gans. I confess that under deadline pressure, I wrote the rather lame quotes attributed to Jerry and Bob. I did show them drafts to get their approval. Preoccupied with other things, each took a quick look and said it was fine. |

|

|

Furman's all-time best-seller

The phenomenal |

|

|

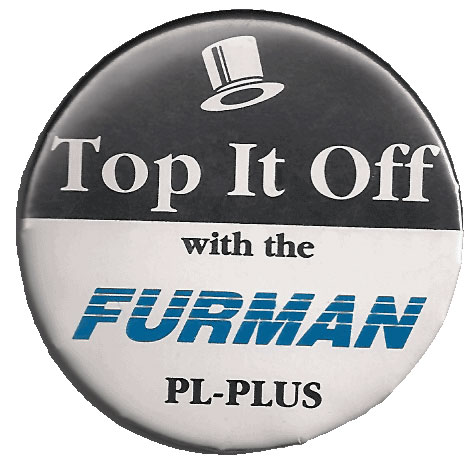

Button from a marketing campaign

Sensing that we were riding a wave, the Furman contingent at the 1986 NAMM show all wore rented top hats and handed out these buttons. The idea was that the top slot in every equipment rack should be occupied by a PL-8 or PL-PLUS. |

|

|

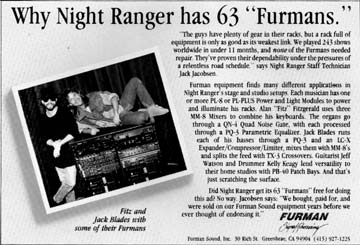

Night Ranger Endorsement Ad

This half-page ad featured Allan "Fitz" Fitzgerald and Jack Blades from the stalwart 80's band, Night Ranger. They really did have 63 Furmans. They were among our biggest fans and often hung out at the Furman factory in Greenbrae. From about 1992. |

|

|

Furman's custom built headquarters in Petaluma, California,

completed January, 1997

|

|

|

Furman Website

The logo at the top of this page (the black rackmount box with the gold "Furman") was created for and used in an earlier version of the website. It was a favorite of mine, so I brought it back to life here. |

|

|